本期经济学人杂志【欧洲】板块下这篇题为《Why the pay gap in Germany is so large》的文章关注的德国男女工资差距较大的问题。

德国女性的工资中位数为 17.09 欧元,比男性(21.60 欧元)少 21%,男女工资差距之大在欧盟内仅次于爱沙尼亚。

相比男性,女性更有可能去从事待遇较低的服务业工作,比如有 2/3 的女性从事售货员工作。一半的女性做的是非全日制工作,这让她们在职场升职更慢,相比之下在男性中这一比例只有 9%。

文章认为,人们选择从事什么样的职业,以及是否从事非全日制工作都是个人的选择,但除此之外也会受到税收福利政策、教育习惯、儿童看护政策和社会规范的影响。

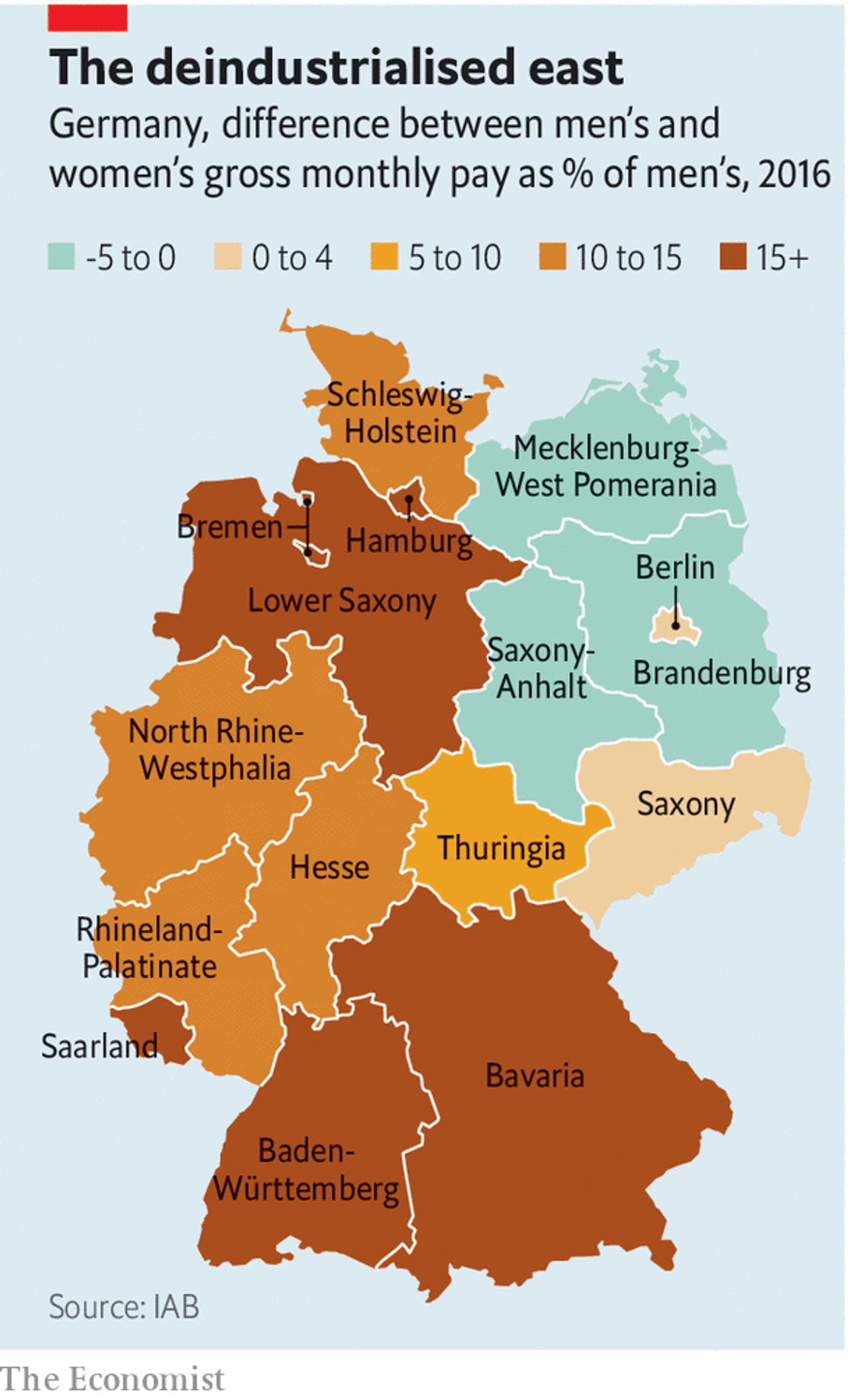

- 德国南部州内男女间的工资差距更大。像 Bavaria 和 Baden-Württemberg 等地从事赚钱的技术和制造业工作的主要是男性。

- 受以前共产主义政策的影响,德国东部的女性较西部女性更有可能去工作。

- 德国女性在生育小孩十年后的平均工资要比以前减少 2/3,但这比儿童看护政策更好的瑞士和法国减少得更多。

- 税收规则和教育习惯(很多学校在午后就放学了)也促使大量女性去从事非全日制的工作。

为此德国也在努力改变,如在 2015 年出台了最低工资法案,更多地帮助女性;新的透明规则要求企业面对员工询问时应当解释工资决定等。

文章最后认为,德国仍有许多工作可以做,比如目前只有 36% 的德国男性休陪产假,应当鼓励男性承担更多孩子抚育的工作等。

Why the pay gap in Germany is so large

From peer to maternity

Why the pay gap in Germany is so large

Women are more likely to work part-time—except in the east

Europe

Mar 14th 2020 edition

Mar 14th 2020

BERLIN

“REVOLUTIONARY” IS not a word that often escapes Angela Merkel’s lips. Yet on March 8th, international women’s day, that was how Germany’s chancellor described the change she had observed in men’s attitudes to balancing work and family. This matters in a country that can still deride Rabenmütter (“Raven mothers”), women who supposedly neglect children for career. But on another measure of equality—pay—Germany is lagging.

The median hourly wage for German women is €17.09 ($19.31), 21% less than men’s €21.60. In the European Union, only Estonia has a wider gap. But the raw numbers can mislead. Adjust for sector, skills, age and other factors, and the gap plummets to 6-7%. Women are likelier than men to work in badly paid service jobs; two-thirds of shop assistants are female. Almost half of working women are part-time (compared with 9% of men) and so tend not to climb the career ladder as fast. Katharina Wrohlich at the German Institute for Economic Research notes that some countries with lower pay gaps, such as Italy, have far fewer women working. Women who earn low wages drag down the average; those who earn nothing are not counted.

Yet the adjusted figures leave something out, too. Which career to follow, and whether to work part-time, are individual choices. Yet they are influenced by tax and benefit rules, education and child-care policy, and social norms. Ensuring equal pay for equal work would not, in itself, make Germany’s boardrooms less male, or get more women into well-paid sectors.

In the former East Germany, the unadjusted pay gap between men and women is minuscule. In some areas, women earn more. This is partly explained by the lack of industrial giants in the east. Germany’s pay gap yawns widest in the humming southern states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, where men dominate lucrative technical and manufacturing jobs. In the east the public sector, where women do better, employs more people. History counts, too. The old communist regime cajoled women to work outside the home, and started a tradition of state-backed child care that persists. East German women have long been more likely to work than westerners, although the figures are converging.

The pay gap has almost vanished for full-time workers under 30, the average age for new mothers, but for those over 40 it has barely budged for three decades. The motherhood wage penalty is higher in Germany than in many rich countries; ten years after giving birth the average German mother earns almost two-thirds less than before, a far more precipitous drop than in countries with better child-care provision, such as Sweden or France. Tax rules and education practices, including schools that can close as early as noon, nudge large numbers of women into part-time work.

Germany is changing. Since 2013 the state has guaranteed day care for children over 12 months (though finding a spot can be nightmarish). The minimum wage, which was introduced in 2015, disproportionally helped women. New transparency rules oblige big firms to explain pay decisions to curious staff. But much remains to be done, including chivvying men to take on more of the duties of parenting; just 36% of German fathers take paternity leave. The revolution is incomplete. ■

This article appeared in the Europe section of the print edition under the headline"Why Germany’s pay gap is so large"