经济学人网站【商业】板块中这篇题为《The impact of covid-19 on airlines》的文章关注的是不断扩散的新冠肺炎疫情对全球航空公司的影响。

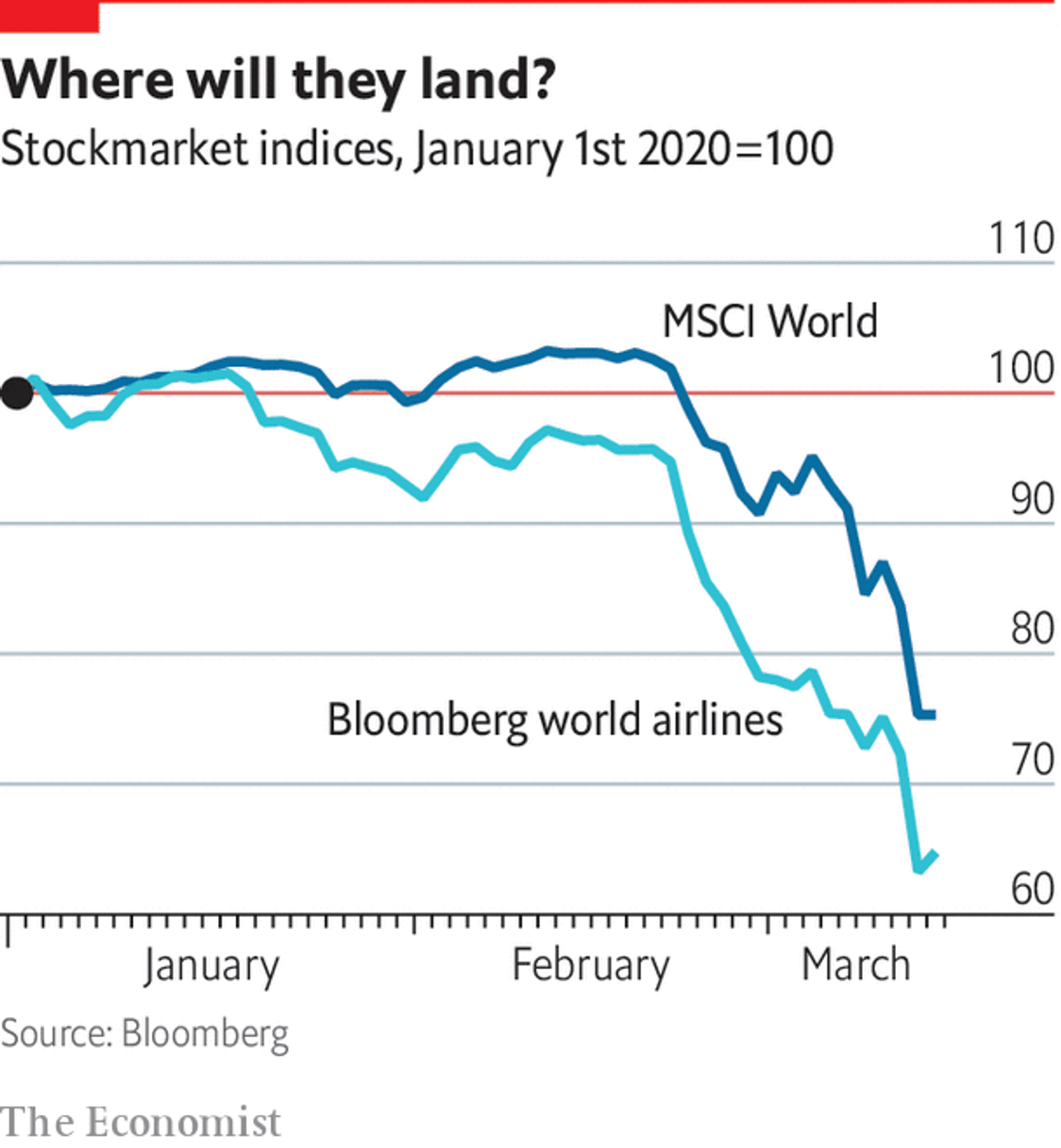

此次新冠肺炎疫情给航空公司带来巨大损失,股价暴跌速度和深度都令人吃惊。欧美航空公司股价下跌的幅度要远大于明晟全球股指。

美国刚发布的欧洲赴美旅行禁令以及因疫情影响人们减少出行,都将减少航空公司的收入。国际航空运输协会(IATA)最近预计,疫情将造成 1,130 亿美元的收入损失,这一数字是去年总收入的 1/5;此外,这比今年 2 月估计的损失多了 4 倍。去年为航空公司带来 200 亿美元收入的赚钱的跨大西洋航线将受到 3 月 14 日生效的欧洲赴美旅行禁令的影响。

欧盟如果作为一个单一航空市场来看的话看起来比较大,但区域内市场分割得很零散,更何况像丹麦、波兰等国已开始禁止非国民进入。欧洲最大航空公司——汉莎航空(Lufthansa)已将 4 月的航班减少一半。

据估计,在 2 月中旬疫情最严重的时候,中国有 70% 的航班停飞。随着疫情逐渐稳定,外加受机票打折力度大的刺激,机场容量较一年前下降 43%。亚洲航空公司依赖来往中国的客流,国泰航空已将 3、4 月的运力下调了 65%,预计 5 月会下调更多。此外,大韩航空也已取消了 80% 的航班。

当前,航空公司都绝望地采取一些措施节省资金,如减少航班、强迫员工休无薪假、临时解雇员工、停发股息等。为帮助挪威航空,挪威政府取消了航空税。航空公司延缓购买新飞机,对已经预定的则请求空客和波音延迟交付。

并非所有的航空公司都能在此次新冠病毒全球大流行中生存下来。3 月 5 日,英国一家有潜在财务问题的名叫 Flybe 的公司宣告破产。据花旗银行称,在零散的欧洲航空市场上,2019 年 1/3 的小航空公司不是亏钱就是几乎破产了。

文章认为,即使幸存下来了,公司将面对更小的航空市场和拥有更多定价权利。在航空运力本就过剩的欧洲,只有那些资产负债表强劲的航空公司才会受益,像挪威航空等弱小的公司可能会成为被收购的目标。如果更多航空公司倒闭,那可能会在航工业引发更广泛的连锁反应。

The impact of covid-19 on airlines

Grounded

The impact of covid-19 on airlines

The aviation industry may not fully recover from the effects of coronavirus

Business

Mar 15th 2020

IT IS NO surprise that the industry clobbered hardest by the covid-19 pandemic is the one responsible for helping spread it to the four corners of the Earth. But the speed and depth of the nosedive which airlines have taken is nevertheless breathtaking. In a memo to staff on March 13th, entitled “The Survival of British Airways”, the carrier’s boss, Alex Cruz, spoke of “a crisis of global proportions like no other we have known”. Most of the industry should pull through if the situation lasts one or two quarters. Any longer, and the future of air travel could be altered for good.

The immediate pain is evident. European and American carriers’ share prices have declined faster even than the globe’s covid-struck stockmarkets (see chart 1). Revenues are in free fall as travel restrictions mount and as fear of infection puts people off spending hours with others in enclosed spaces. On March 5th the International Air Transport Association (IATA), a trade group, projected a possible hit to worldwide revenues of up to $113bn this year. That is one-fifth of last year’s overall revenues and four times higher than IATA estimated in February, when the coronavirus was still believed to be a Chinese problem rather than a global one.

Since IATA’s revision things have got worse. Lucrative transatlantic routes, which earned airlines around $20bn in sales last year, have been hit by President Donald Trump’s 30-day ban on most flights to America from Europe, which took effect on March 14th. Delta, an American carrier, says it may have to trim international schedules by 40%, up from a 25% reduction before the ban. Lufthansa, Europe’s biggest carrier, had already cut flights in half for April. As more countries impose travel restrictions, the German airline may need to thin schedules by 90%, reckon analysts at Bernstein, a research firm. Others that serve smallish domestic markets and rely on global interconnections may need to shut down altogether.

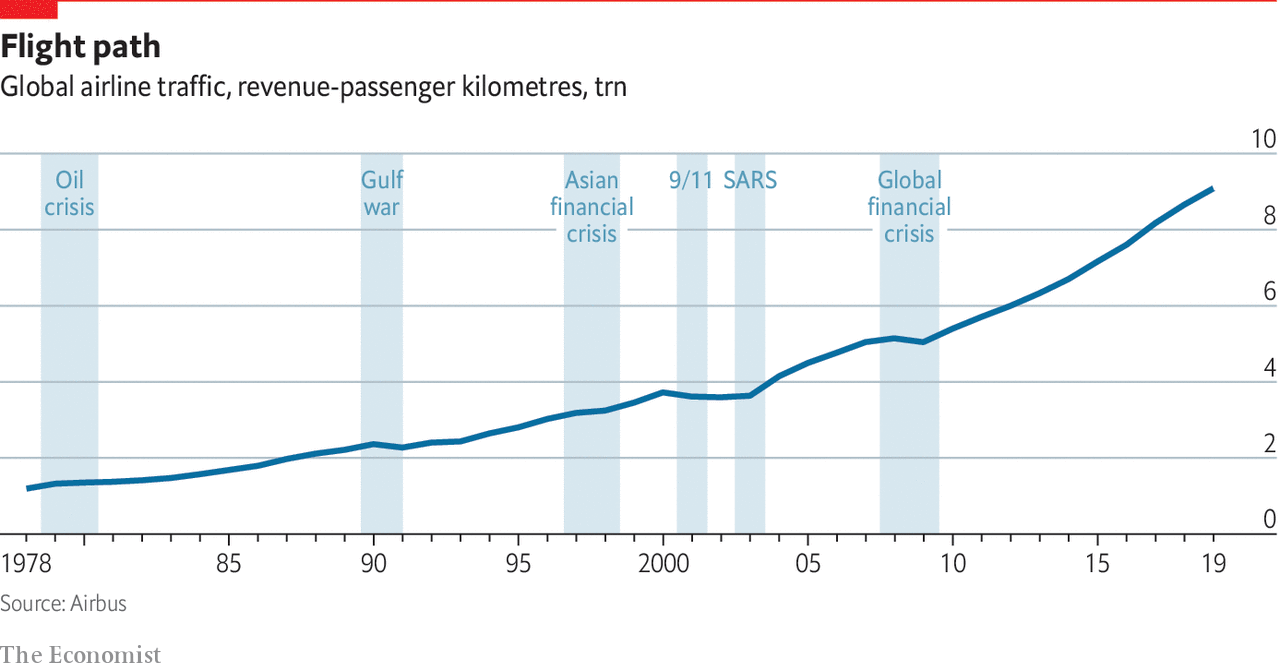

Many airline bosses cling to the hope that global passenger numbers will follow the same trajectory as in the wake of previous disruptions, such as the terrorist attacks of September 11th 2001 or the global financial crisis of 2007-09 (see chart 2). After a few months of disarray, travel patterns then reverted to normal and growth resumed.

That, more or less, is what has happened in China this year. Chinese carriers were hit hard at first. At the peak of the outbreak in mid-February around 70% of flights were grounded, according to OAG, a travel data firm. Now that infections are stabilising in the country Chinese passengers are getting back in the air, tempted by large discounts. The latest data suggest that capacity is now down by 43% compared with a year ago.

Few airlines, though, serve a vast domestic market like China’s. Only America’s is larger. The European Union’s single aviation market looks large, but is fragmenting as member states put up barriers; Denmark and Poland have already barred most non-citizens from entering, for example. Asian airlines that rely on traffic to and from China, but not within it, are still reeling. Cathay Pacific, based in Hong Kong, has cut capacity by 65% in March and April, and anticipates more cuts in May. Korean Air has lopped 80% of its schedule. Like BA’s Mr Cruz, it warns that a prolonged disruption presents an existential threat.

Chinese airlines can also count on generous government support. Most of the big ones are state-owned (China Eastern and China Southern) or could be (there was speculation last month that struggling Hainan Airways’ parent company, HNA, may be nationalised). Beijing has already promised bail-outs to make up for their losses, estimated to be around $3bn in February alone.

Lufthansa is talking to European governments about financial support. That may require relaxing EU state-aid rules. Mr Trump’s vague talk of assistance to stricken industries, including airlines, remains just that for now.

At the moment most airlines are desperately trying to preserve cash. Besides cutting flights, many are asking or forcing staff to take unpaid leave. Norwegian Air Shuttle, an indebted low-cost airline in the midst of restructuring, has temporarily laid off half of its 11,000 workers. Scandinavia’s SAS is laying off 10,000 workers, 90% of its workforce, as it cancels most of its flights. KLM, the Dutch flag carrier, said it would cut 2,000 jobs in the coming months. Lufthansa has suspended its dividend for 2019. It may sell some aircraft. The steep fall in the oil price ought to help, but many airlines will only feel the benefit later, having previously locked in purchases at higher prices to hedge against the risk of pricier fuel.

Governments are offering some assistance. To help Norwegian its home government has removed aviation taxes. In an effort to prevent wasteful ghost flights with no passengers, which some carriers have been flying to preserve valuable take-off and landing slots at busy airports, regulators around the world have temporarily waived rules that require slots to be used at least 80% of the time.

Plenty of carriers are also scaling back capital expenditure by deferring the purchase of new aircraft. Airbus, Europe’s aerospace giant, has agreed to delay some deliveries to Chinese airlines. Cathay is discussing deferrals with both Airbus and its American rival, Boeing. Airlines are also asking leasing companies, which have grown rapidly over the past decades and now own around 50% of the global fleet, to show forbearance over payments.

Not every airline will survive the pandemic. Europe has already seen one casualty. Flybe, a British airline with underlying financial-health issues, declared bankruptcy on March 5th. Norwegian’s share price, which had lost 80% of its value between 2016 and 2019, has now shed another four-fifths since February. In Europe’s fragmented aviation market a third of carriers, mostly small no-frills ones, either lost money or barely broke even in 2019 according to Citigroup, a bank. Carsten Spohr, boss of Lufthansa, predicts “numerous insolvencies”.

Carriers which do make it through will enjoy less crowded skies—and more pricing power. A shake-out in Europe, long plagued by overcapacity, would benefit companies with strong balance-sheets. These include EasyJet, Ryanair and—despite Mr Cruz’s warnings—BA’s parent, IAG. On March 13th the Financial Times reported that two non-executive board members at IAG have loaded up on the group’s cheap shares, suggesting a modicum of confidence in its prospects. Weakened airlines like Norwegian, and possibly even more illustrious liveries, may become acquisition targets.

All that will only happen if the recovery is swift, however. The longer the pandemic lasts, the less certain travel patterns are to revert to normal. In a worrying sign, the boss of one big leasing firm says that even firms with apparently robust balance-sheets have asked him to go easy on rent, suggesting at least some are worried about survival.

If more airlines start to fail, that would have knock-on effects throughout the broader aviation industry. Even before Mr Trump’s prohibition American airport operators were expecting to lose at least $3.7bn between them this year. Weaker airports could come under pressure and may not survive, making some regions less accessible even if conditions eventually improve. Airbus and Boeing are making fewer planes and look likely to rethink plans for ramping up production of narrow-body airliners; falling profits will weigh on efforts to invest in new climate-friendlier models. Even leasing firms, which have plenty of capital and could repurchase planes from straitened airlines and then lease them back, could be hurt if widespread insolvencies flood the market with second-hand aircraft, depressing leasing rates.

Perhaps the greatest uncertainty concerns shifting attitudes to business and leisure travel. If corporations detect that they can operate with fewer executives flitting round the globe, and holidaymakers get a taste for “staycations” or trains, compounded by “flight shame” over aeroplanes’ carbon emissions, the industry may struggle to keep doubling passenger volumes every 15 years, as it has done for the past three decades. The coronavirus is already proving to be quite the braking parachute. It may arrest momentum more dramatically still.