经济学人杂志 2021 年 1 月 18 日【经济金融】板块下这篇题为《China's economy zooms back to its pre-covid growth rate》的文章关注的是 2021 年 1 月 18 日中国国家统计局公布的 2020 年度经济“成绩单”。

2021 年 1 月 18 日公布的经济数据显示,2020 年中国经济全年增长率为 2.3%,其中第四季度经济同比增长 6.5%,甚至超过了疫情前的水平;全年贸易顺差达 5,350 亿美元,同比增长 27%。

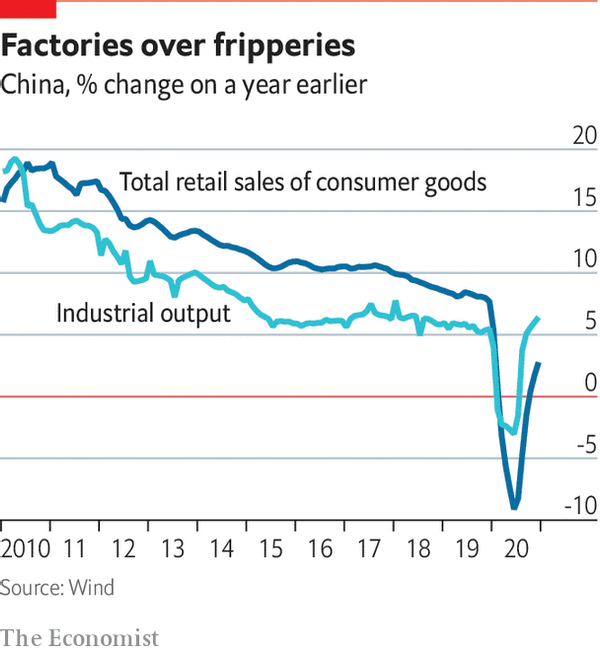

同时也存在消费需求恢复不足等挑战,2020 年中国规模以上工业增加值同比增长 2.8%,社会消费品零售总额同比下降 3.9%,文章认为生产和消费的分化部分与中国早在 2020 年 2 月就开始谨慎重启工厂,但在近半年后才完全重启学校等有关。

2020 年城市人均可支配收入同比上涨 1.2%,增速只有 GDP 的一半,文章认为部分是因为与发达国家会直接向个人提供支持不同,中国的财政刺激政策倾向于支持基础建设和向企业发放贷款,希望企业招聘更多人,提高工资等。

文章最后认为,与 2020 年中国经济数据相比,中国在应对新冠疫情局部爆发时不遗余力(spare no effort)地果断处理方式更值得关注。其他国家要想恢复经济,首先应当控制住疫情的蔓延。

注一: 国家统计局 《2020 年国民经济稳定恢复,主要目标完成好于预期》

China's economy zooms back to its pre-covid growth rate

Viral expansion

China’s economy zooms back to its pre-covid growth rate

Its success offers some useful lessons about how to confront a pandemic

Finance & economics

Jan 18th 2021

SHANGHAI

IN THE EARLY months of the covid-19 outbreak, researchers at the Federal Reserve and Massachusetts Institute of Technology published a paper entitled “Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not”. Examining America’s response to the influenza pandemic that broke out in 1918, they concluded that cities that acted early and forcefully had the best economic outcomes. Those that delayed such measures could not escape the pandemic’s shadow: people still curbed their consumption and businesses capped their investment. Cities that imposed strict controls, by contrast, limited the damage to public health and were able to bounce back sooner.

Economists will pore over data from the covid-19 shock for years to come. But China’s GDP figures for 2020, published on January 18th, suggest that the researchers’ findings from the influenza of 1918 were spot on. After its early fumbles in managing the novel coronavirus outbreak, China imposed stricter lockdowns than just about any other country. The new data confirm that it was one of a handful of countries to register any economic growth at all last year.

China’s GDP expanded at an annual rate of 2.3% in 2020 as a whole. Anyone predicting such a pace before the pandemic would have sounded outlandishly gloomy; it is, by some distance, China’s weakest growth rate since 1976, the final year of the Cultural Revolution. In the covid-blighted world, though, things look different. More impressive yet is China’s momentum. In the fourth quarter of 2020 growth accelerated to 6.5%, year on year, faster than its pre-covid rate. With vaccines being rolled out and the base of comparison very low at the start of the year, growth could soar to nearly 20% in the first quarter of 2021.

Nevertheless, the strength of the headline rebound has masked both big imbalances and the difficulties faced by many in China. The industrial sector was the first part of the economy to recover, and has remained its brightest spot. Factory output increased by 2.8% in 2020 compared with 2019. At the other end of the spectrum was the fall of 3.9% in retail sales—a proxy for consumption and a reflection of the way people feel about their prospects (see chart).

The divergence between production and consumption partly stems from the way that China sequenced its economic restart. The government believed, correctly, that it would be easier to contain viral risks in factories, which function as semi-closed ecosystems, often with workers living in nearby dormitories. As early as February, when other countries were just grasping the sheer scale of the health crisis, China carefully reopened its factory gates. It was nearly half a year later before it fully reopened schools.

Chinese factories also benefited from developments in the global economy, distorted and depressed though it was by the pandemic. Between March and the end of 2020 China exported 224bn masks, enough for 35 per person around the world. And its companies were big exporters of the screens and sofas in high demand as people spent far more time at home. As a result China’s merchandise trade surplus hit $535bn last year, up by 27% from 2019 and just shy of a record.

But sluggish consumption at home points to the gloomier side of China’s recovery. In rich countries many governments dramatically increased fiscal support for people who lost jobs during the pandemic. China instead focused its stimulus spending on new infrastructure projects and on cheap loans to companies, hoping that they, in turn, would hire workers and thus support wages. By the end of the year the government could boast that the unemployment rate in cities had returned to 5.2%, the same as at the end of 2019. Wages, though, took a hit. In cities disposable income per person increased by just 1.2% last year, half as fast as GDP growth. Many migrant workers suffered pay cuts.

Inequality also seems to have worsened. As in many other countries, 2020 was lucrative for the wealthy. Asset prices soared, thanks in part to the central bank’s loosening of monetary policy. The CSI 300 index, a gauge of China’s biggest stocks, rallied by nearly 30%, while property prices in the country’s main cities rose at their fastest pace since 2017. In recent weeks, buoyed by the strength of the economy and wary about the red-hot markets, the government has gradually started tapering its stimulus. China’s overall debt-to-GDP ratio shot up by about 25 percentage points last year, climbing to nearly 290%. This year, with credit growth slowing, the debt ratio should stabilise.

Ultimately, though, the good and bad of China’s economic policies in 2020 were far less important than its decision to spare no effort to eliminate covid-19. A small outbreak currently under way in Hebei, a northern province, has once again demonstrated its approach: rapid testing on a mass scale; detailed contact tracing through smartphone apps; limits on travel between regions; and strict quarantines wherever infections are detected. Other countries understandably shy away from such tactics, enabled as they are by China’s authoritarian politics. But they are an extreme version of what should now be recognised as best practice when a pandemic strikes. The crucial first step, from which all else follows, is to try to stop its spread. That was true in 1918—and was again in 2020.