本期经济学人杂志【经济金融】板块下这篇题为《America wants the World Bank to stop making loans to China》的文章关注的是特朗普等美国政客批评世界银行向中国借钱,但世行向中国贷款的规模实际上很小,且利息相对较高,世行从中获利颇丰。

世行目前向中国的贷款总额为 147 亿美元,在接下来的五年里计划向中国每年借款 10~15 亿美元,这要比 2015~2019 年平均少 15~40%。

世行借给中国的钱被用于财政改革、私营企业、社会支出以及环境改善领域,如果能帮助中国走向清洁增长之路,那这对包括中国的地缘政治对手在内的所有人都好。

由于利息相对较高,去年世行从向中国的贷款中赚了 1 亿美元的利润,这可以用于帮助更贫穷的国家。其实中国完全可以依靠自己用成本更低的方式来筹钱,比如发行收益率低的主权债券等。

文章认为,很难解释中国为什么非要向世行借钱,毕竟借款总额只有中国 GDP 的 0.01%。一个可能的解释是,也许中国想通过借款从世行学习诸如评估审核资质、如何经营银行等方面的知识吧。::quyin:1huaji::

America wants the World Bank to stop making loans to China

A profitable student

America wants the World Bank to stop making loans to China

It left deep poverty behind long ago. But the loans make the bank a tidy profit

Print edition | Finance and economics

Dec 12th 2019| HONG KONG

The caribbean islands of St. Kitts and Nevis are known for luxury tourism (visitors include Meryl Streep and Oprah Winfrey), pricey citizenship (on sale for $150,000), and a sprint world champion (Kim Collins). But despite the country’s many assets (including a national income per person of over $18,000) it is eligible for loans from the World Bank, an institution dedicated to eradicating extreme poverty.

Because the islands are so small, this draws little comment. Not so for China. Its income per person is half that of St. Kitts and Nevis, and lower than that of Poland, Malaysia, Turkey and 15 other potential borrowers. But its eligibility to borrow from the World Bank strikes many Americans as anomalous, even scandalous.

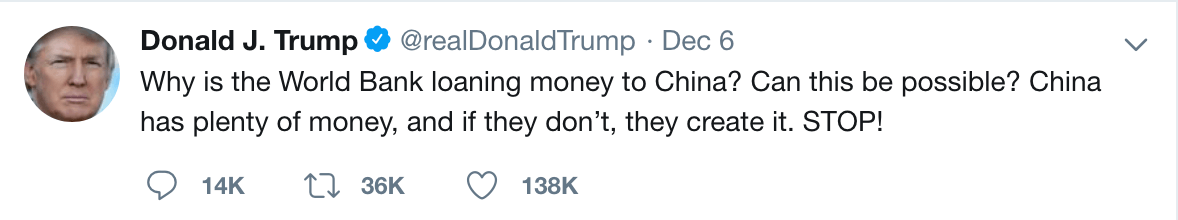

One of them is President Donald Trump. “Why is the World Bank loaning money to China? Can this be possible?” he tweeted on December 6th, a day after the bank discussed a new five-year lending framework for America’s rival. Another used to be the World Bank’s president, David Malpass, in his former job as an American treasury official. In 2017 he argued that “it doesn’t make sense to have money borrowed…using the us government guarantee, going into lending in China”. Steven Mnuchin, the treasury secretary, heard similar sentiments in a congressional hearing on December 5th. “What are you doing to stop those loans?” asked a Democrat. “It’s unconscionable to me that our taxpayers should...be subsidising the Chinese growth model,” said a Republican. On this question, at least, America’s legislature is almost as harmonious as its Chinese counterpart.

America had objected to the new framework, Mr Mnuchin said. But it cannot have surprised him. In a deal struck last year, America agreed to an increase in the bank’s capital, in return for which the bank agreed to charge its richer borrowers higher interest rates, lend to them more sparingly and encourage more of them to “graduate” (ie, cease to be eligible for the bank’s loans).

But graduating from the bank is like graduating from a German university: neither brisk nor uniform; leaving behind many dauerstudenten (eternal students). Once a country reaches a national income of $6,975 per person, a “discussion” begins. The bank also considers a country’s access to capital markets and the quality of its institutions. Of the 17 countries that have graduated since 1973, five later sank back into eligibility, according to a study by the Policy Centre for the New South, a Moroccan think-tank. South Korea left in 1995, then needed the bank’s help in the Asian financial crisis. It remained eligible for further loans until 2016, when its income per person was almost three times China’s current level.

The bank will, however, lend to China more selectively. The country now owes it about $14.7bn. Over the next five years, it envisages lending $1bn-1.5bn a year, 15-40% less than it averaged in 2015-19. The new money aims to encourage fiscal reforms, private enterprise, social spending and environmental improvements. If the bank can help nudge China towards cleaner growth that will benefit everyone, including China’s geopolitical rivals. It also hopes to finance pilot projects that poorer countries can learn from. It has paid for Ethiopian officials to study China’s irrigation and Indian officials to study its trains.

But would the money not be better spent in poorer countries themselves? The bank’s friends point out that its lending to China earns a tidy profit (roughly $100m last year). It charges China a higher interest rate than it pays on its own borrowing. That is money that can then be used to help poor people who live elsewhere.

In theory, its donor governments could do all this more cheaply and simply themselves. They could issue an equivalent amount of low-yielding sovereign bonds, buy higher-yielding emerging-market securities and donate any profits to low-income countries. But that is not what critics of China’s lending are proposing.

Given the profits it can earn, the bank is eager to keep lending to China. Harder to explain is why China wants to keep borrowing from the bank. The sums are small (0.01% of gdp) and the process can be cumbersome. China may value the bank’s expertise. But if so, why not buy it without a loan attached?

There are examples of China doing just that. It bought advice on how to improve in the bank’s assessment of the ease of doing business. But China may feel a loan gives the bank more skin in the game. Consultants paid only for advice can always blame disappointments on poor implementation of their sound prescriptions. A lender has a greater stake in solving difficulties. Institutions like the bank and the imf stress the importance of borrowers taking “ownership” of reform programmes. China may feel the same about the lenders it deigns to borrow from.■

This article appeared in the Finance and economics section of the print edition under the headline"A profitable student"