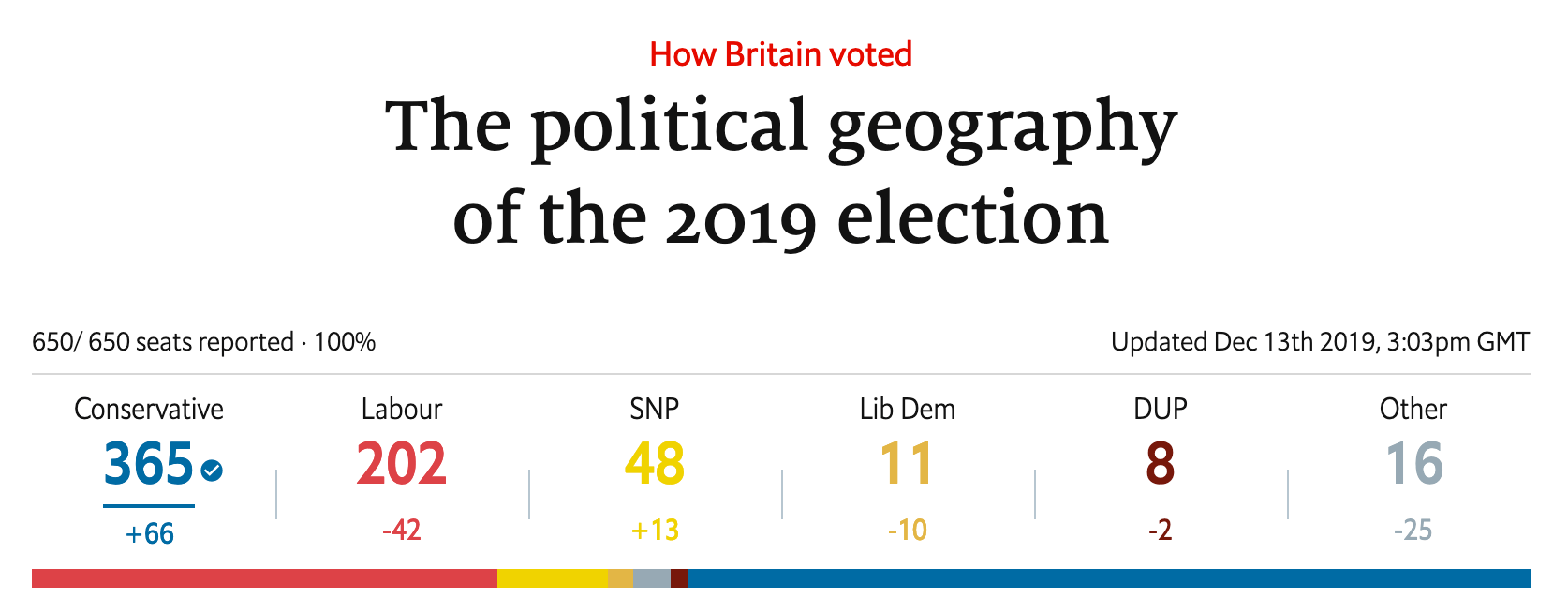

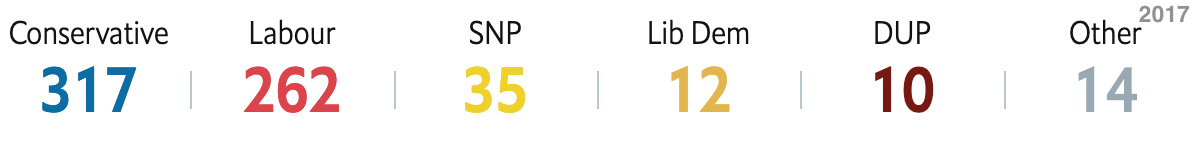

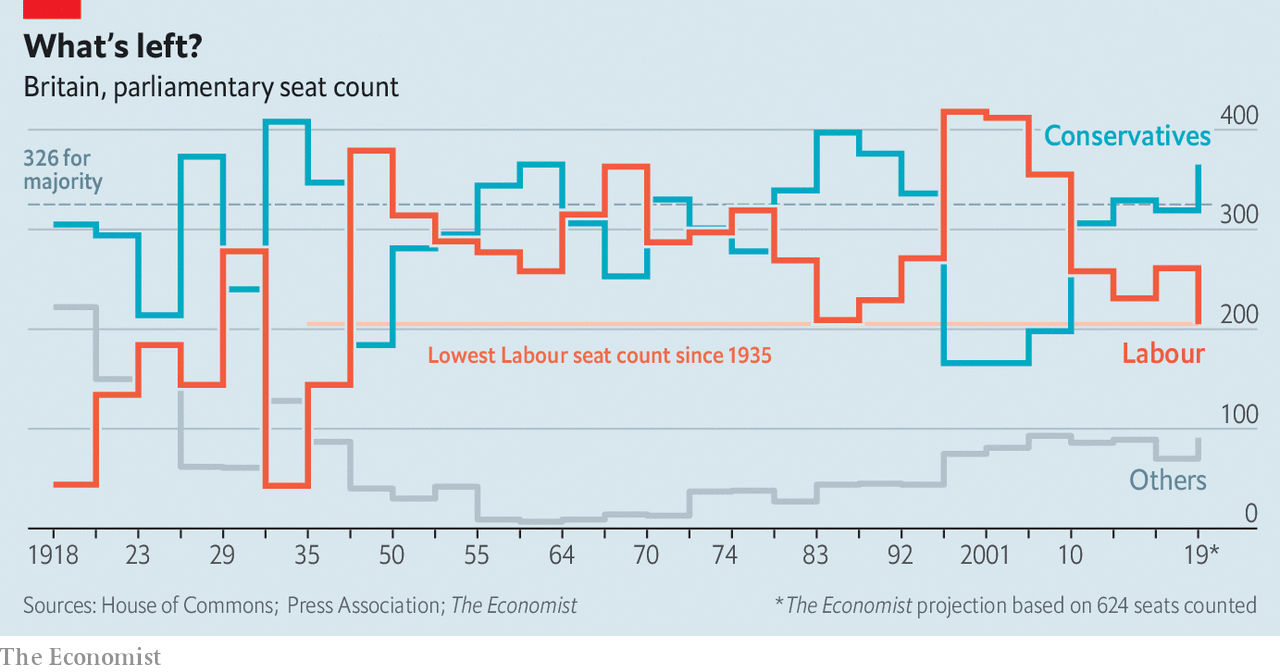

本期经济学人杂志【经济金融】板块下这篇题为《Victory for Boris Johnson’s all-new Tories》的文章关注的是 2019 年英国大选结束,首相鲍里斯·约翰逊 (Boris Johnson) 领导的保守党取得压倒性胜利。此次大选中约翰逊赢得了英格兰北部和中部许多工党传统支持者的选票。文章认为,富人阶层和普通工薪阶层支持下的全新的保守党虽然控制了议会,但仍需要做很多工作来巩固它。

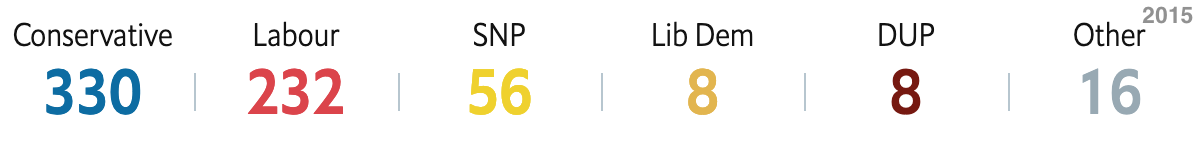

此次选举是执政保守党 1987 年以来最大的胜利,是最大反对党工党自 1935 年以来最严重的失败,并且工党在英国政坛将会消沉很长一段时间。此次大选的直接结果是,自 2016 年脱欧公投以来第一次确定——英国将在明年一月底脱离欧盟。

此次大选中,反对党工党在北部的传统选区被保守党侵蚀,工薪阶层转而把票投给了保守党。保守党领袖——首相约翰逊在经济上向“左”,承诺增加公共支出,对困难行业给予政府救助;在文化上向“右”,呼吁更长的监禁刑罚,抱怨移民等。

美国总统特朗普早就展示了文化上持保守态度是如何能团结好富人和穷人选民的。

文章认为,富人阶层和普通工薪阶层支持下的全新的保守党虽然控制了议会,但仍需要做很多工作来巩固它。比如为了留住北部选民,约翰逊不得不在基建、医疗和福利上加大支出,并且收紧移民政策。脱离欧盟后与欧盟的协议谈判的好坏会影响英国未来的发展。

此次大选中苏格兰民族党 (SNP) 在议会的席位也增加了 13 席,该党党魁尼古拉·斯特金形容选举结果显示,约翰逊不能把苏格兰带离欧盟,苏格兰应该再次举行独立公投,决定自己的未来。

Victory for Boris Johnson’s all-new Tories

Britain’s election

Victory for Boris Johnson’s all-new Tories

The Conservatives’ capture of the north points to a realignment in British politics. Will it last?

BRITAIN’S ELECTION on December 12th was the most unpredictable in years—yet in the end the result was crushingly one-sided. As we went to press the next morning, Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party was heading for a majority of well over 70, the largest Tory margin since the days of Margaret Thatcher. Labour, meanwhile, was expecting its worst result since the 1930s. Mr Johnson, who diced with the possibility of being one of Britain’s shortest-serving prime ministers, is now all-powerful.

The immediate consequence is that, for the first time since the referendum of 2016, it is clear that Britain will leave the European Union. By the end of January it will be out—though Brexit will still be far from “done”, as Mr Johnson promises. But the Tories’ triumph also shows something else: that a profound realignment in British politics has taken place. Mr Johnson’s victory saw the Conservatives taking territory that Labour had held for nearly a century. The party of the rich buried Labour under the votes of working-class northerners and Midlanders.

After a decade of governments struggling with weak or non-existent majorities, Britain now has a prime minister with immense personal authority and a free rein in Parliament. Like Thatcher and Tony Blair, who also enjoyed large majorities, Mr Johnson has the chance to set Britain on a new course—but only if his government can also grapple with some truly daunting tasks.

A cold coming they had of it

On a rainswept night the Conservatives marched into constituencies long seen as Labour strongholds (see Britain section). Blyth Valley, an ex-mining community in the north-east where Tories have for generations been the enemy, fell before midnight. Wrexham, Labour turf for more than 80 years, declared for the Conservatives at 2am. Great Grimsby, a struggling northern port held by Labour since the second world war, was taken soon after. By dawn it was clear that the “red wall” of Labour constituencies, which stretched unbroken from north Wales to Yorkshire, had been demolished.

Mr Johnson was lucky in his opponent. Jeremy Corbyn, Labour’s leader, was shunned by voters, who doubted his promises on the economy, rejected his embrace of dictators and terrorists and were unconvinced by his claims to reject anti-Semitism.

But the result also vindicates Mr Johnson’s high-risk strategy of targeting working-class Brexit voters. Some of them switched to the Tories, others to the Brexit Party, but the effect was the same: to deprive Labour of its majority in dozens of seats.

Five years ago, under David Cameron, the Conservative Party was a broadly liberal outfit, preaching free markets as it embraced gay marriage and environmentalism. Mr Johnson has yanked it to the left on economics, promising public spending and state aid for struggling industries, and to the right on culture, calling for longer prison sentences and complaining that European migrants “treat the UK as though it’s basically part of their own country.” Some liberal Tories hate the Trumpification of their party (the Conservative vote went down in some wealthy southern seats). But the election showed that they were far outnumbered by blue-collar defections from Labour farther north.

This realignment may well last. The Tories’ new prospectus is calculated to take advantage of a long-term shift in voters’ behaviour which predates the Brexit referendum. Over several decades, economic attitudes have been replaced by cultural ones as the main predictor of party affiliation. Even at the last election, in 2017, working-class voters were almost as likely as professional ones to back the Tories. Mr Johnson rode a wave that was already washing over Britain. Donald Trump has shown how conservative positions on cultural matters can hold together a coalition of rich and poor voters. And Mr Johnson has an extra advantage in that his is unlikely to face strong opposition soon. Labour looks certain to be in the doldrums for a long time (see Bagehot). The Liberal Democrats had a dreadful night in which their leader, Jo Swinson, lost her seat.

Yet the Tories’ mighty new coalition is sure to come under strain. With its mix of blue collars and red trousers, the new party is ideologically incoherent. The northern votes are merely on loan. To keep them Mr Johnson will have to give people what they want—which means infrastructure, spending on health and welfare, and a tight immigration policy. By contrast, the Tories’ old supporters in the south believe that leaving the EU will unshackle Britain and usher in an era of freewheeling globalism. Mr Johnson will doubtless try to paper over the differences. However, whereas Mr Trump’s new coalition in America has been helped along by a roaring economy, post-Brexit Britain is likely to stall.

Any vulnerabilities in the Tories’ new coalition will be ruthlessly found out by the trials ahead. Brexit will formally happen next month, to much fanfare. Yet the difficult bit, negotiating the future relationship with Europe, lies ahead. The hardest arguments, about whether to forgo market access for the ability to deregulate, have not begun. Mr Johnson will either have to face down his own Brexit ultras or hammer the economy with a minimal EU deal.

As he negotiates the exit from one union he will face a crisis in another. The Scottish National Party won a landslide this week, taking seats from the Tories, and expects to do well in Scottish elections in 2021. After Brexit, which Scots voted strongly against, the case for an independence referendum will be powerful. Yet Mr Johnson says he will not allow one. Likewise in Northern Ireland, neither unionists nor republicans can abide the prime minister’s Brexit plans. All this will add fuel to a fight over whether powers returning from Brussels reside in Westminster or Belfast, Cardiff and Edinburgh. The judiciary is likely to have to step in—and face a hostile prime minister whose manifesto promises that the courts will not be used “to conduct politics by another means or to create needless delays”.

Led all that way for birth or death?

There is no doubting the strength of Mr Johnson’s position. He has established his personal authority by running a campaign that beat most expectations. His party has been purged of rebels, and their places taken by a new intake that owes its loyalty to him personally. Having lost control of Parliament for years, Downing Street is once more in charge.

Mr Johnson will be jubilant about the scale of his victory, and understandably so. But he should remember that the Labour Party’s red wall has only lent him its vote. The political realignment he has pulled off is still far from secure.

Dig deeper:

Our latest coverage of Britain’s election